The real difference between a pot still and a column still boils down to two things: process and purpose. Traditional pot stills are all about creating rich, complex whiskies in small, deliberate batches. This method keeps more of the flavorful oils and compounds, giving you a heavier, more character-driven spirit, something many American craft whiskey producers are famous for.

On the flip side, modern column stills are built for efficiency. They operate continuously to produce a lighter, smoother, and incredibly consistent spirit. This makes them the workhorses of the industry, perfect for large-scale production and creating the approachable profiles many new whiskey drinkers enjoy.

Understanding How Stills Shape Your Whiskey

Ever wondered what gives your favorite whiskey its soul? More often than not, the story starts with the still. The specific type of distillation equipment is one of the most critical decisions a distiller makes, and it directly shapes the final flavor, aroma, texture, and even the price of the whiskey in your glass.

This guide is here to unpack the essential differences between these two foundational pieces of equipment. Think of a pot still like an artist's chisel, carefully sculpting a spirit loaded with personality. A column still, in contrast, is more like a high-precision instrument, engineered for consistency and scale.

The Core Distinctions

Choosing between a pot and column still is really a choice between two different philosophies of making spirits. One approach chases complexity and character, while the other is all about efficiency and purity. This core distinction is exactly why certain styles of whiskey are almost exclusively tied to one type of still.

Let's break down the key differences at a high level.

Pot Still vs Column Still At a Glance

The table below offers a quick snapshot of the fundamental characteristics of each still type. Think of it as your cheat sheet for understanding how the initial distillation process sets the stage for everything that follows.

| Characteristic | Pot Still | Column Still |

|---|---|---|

| Process Type | Batch (one distinct run at a time) | Continuous (non-stop, 24/7 operation) |

| Flavor Profile | Rich, complex, full-bodied, oily | Light, smooth, clean, delicate |

| Alcohol Proof | Lower (approx. 60-80% ABV) | Higher (up to 96% ABV) |

| Efficiency | Lower yield, more labor-intensive | High yield, highly automated |

| Commonly Makes | Single Malt Scotch, Irish Whiskey, Craft American Whiskey | Most Bourbon, Rye, Canadian, and Grain Whiskey |

As you can see, the divergence is stark. A pot still run is a hands-on, sensory-driven event for the distiller, while a column still run is a masterpiece of engineering and control.

This fundamental choice in distillation equipment dictates everything that follows.

Why It Matters for New Whiskey Drinkers

For anyone just starting their whiskey journey, getting a handle on this difference is like finding a key to unlock tasting notes.

- Tip for New Drinkers: If you're sipping something heavy, oily, and packed with robust grain flavors, chances are it was born in a pot still. On the other hand, a lighter, smoother whiskey with more delicate, sweet notes probably came from a column still.

Recognizing these traits will seriously deepen your appreciation and help you pinpoint what you truly enjoy in a whiskey. And while these two methods are the most common, distillers are always pushing the envelope. You can learn more about their incredible work by exploring diverse distillation methods in craft whiskey. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for a deeper dive into how metal, shape, and science combine to create the spirit in your glass.

The Craft of Pot Still Distillation

To really get pot still distillation, you have to appreciate it as a timeless, hands-on craft. This is the old-school way of making spirits, built on a simple yet profound principle: separating alcohol from water and other compounds, one controlled batch at a time. It’s a slow, deliberate process that demands immense skill and constant attention from the distiller.

Think of a large, often beautifully ornate, copper kettle. That’s the heart of the pot still. A fermented liquid, what distillers call the "wash" or "distiller's beer," gets heated inside. Since alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, it vaporizes first. This vapor then rises up the still’s neck and is guided over to be condensed back into a liquid spirit.

Unlike its endlessly running counterpart, a pot still has to be stopped, emptied, cleaned out, and refilled after every single run. This batch-by-batch nature is exactly what gives the distiller so much influence over the final product, but it also makes the whole affair far more labor-intensive and less efficient than column distillation.

The Art of the Still’s Shape

The specific geometry of a pot still isn't just for looks; every single curve and angle plays a crucial role in shaping the final flavor. From the rounded base—the "pot" or "kettle"—to the tapering neck and the angle of the "lyne arm," each element influences which flavor compounds actually make it into the bottle.

This is where congeners enter the picture. Congeners are the chemical compounds—esters, aldehydes, and oils—that are responsible for the vast majority of a whiskey's aroma and flavor. A pot still is designed specifically to retain a significant amount of these compounds, creating a spirit that is rich, complex, and full-bodied.

The shape of a pot still is its signature. A taller neck will create a lighter spirit by allowing heavier compounds to fall back down, while a shorter neck produces a richer, oilier whiskey. It’s a game of millimeters that defines the final character.

The Distiller’s Most Important Job: Making the Cuts

During each distillation run, the distiller has to perform the most critical task of the whole process: "making the cuts." The spirit that flows off the still isn’t uniform; it’s separated into three distinct parts:

- The Heads (Foreshots): This is the first liquid to come off the still. It’s packed with volatile compounds like acetone and methanol, which are undesirable and even toxic. The distiller discards or redistills this portion.

- The Heart (The Spirit): This is the prize. The heart cut contains the best-quality ethanol and the most desirable congeners that define the whiskey’s character. This is the liquid that will go into barrels for aging.

- The Tails (Feints): The final part of the run has a lower alcohol content and is heavy with unpleasant, oily compounds. Just like the heads, the tails are cut away and often tossed into the next batch to be redistilled.

The precision of these cuts is an art form honed over years. A wider heart cut might result in a more robust and funky spirit, while a narrower one yields a cleaner, more refined profile. This decision is where a distiller's experience and house style truly shine through.

American Craft Distillers Championing Pot Stills

While column stills absolutely dominate large-scale American whiskey production, a vibrant movement of craft distillers has embraced the pot still to create unique, character-driven spirits. These producers are intentionally trading high-volume efficiency for hands-on control and a greater depth of flavor.

A fantastic example is Balcones Distilling in Texas, which uses copper pot stills to produce its award-winning American Single Malts and bourbons. Their process results in bold, complex whiskies that are distinctly Texan. In the same vein, Westland Distillery in Seattle champions the pot still to express the unique character of Pacific Northwest barley, creating some of the most respected American Single Malts on the market. These distilleries prove that the classic pot still vs column still debate is often a choice between scale and soul.

The Science of Column Still Distillation

If the pot still is the heart of deliberate, hands-on craft distillation, then the column still is the brains of modern, large-scale whiskey production. It's an engine built for one primary purpose: relentless efficiency. Instead of the stop-and-start nature of a pot still, the column still—also called a continuous or Coffey still—runs in a non-stop flow.

Picture a towering, vertical chamber, often shooting several stories into the air, filled with a series of perforated plates. A constant stream of pre-heated fermented mash gets pumped into the top of this column. As it slowly trickles down, it’s met by hot steam rising from the bottom. This is where the real science kicks in.

The rising steam strips the alcohol from the descending mash, creating a vapor that continues its journey up through the column. With each plate it passes, that vapor becomes progressively purer and higher in alcohol, leaving heavier compounds and water to fall back down. It's like having dozens of tiny distillations happening all at once, stacked one on top of the other inside a single massive piece of equipment.

How Continuous Distillation Works

The real genius of the column still is its self-sustaining cycle. The process is a continuous loop of separation, purification, and condensation that can run for days, or even weeks, without a single pause. This incredible design allows for shocking consistency and the production of extremely high-proof spirits on a massive scale.

This constant operation is a major point of difference in the pot still vs column still debate. The invention that made it all possible came in 1830, when an Irishman named Aeneas Coffey patented his continuous column still. This completely revolutionized spirit production by ditching the laborious batch method, allowing distillers to make alcohol at an incredible speed and purity. Some of these stills can reach up to 96% ABV. You can dive deeper into this game-changing moment in the history of distillation technology.

The column still is a workhorse, not a show pony. Its purpose is to create a clean, consistent spirit with unparalleled efficiency, forming the backbone of the world's most popular whiskey styles.

The Engine of American Whiskey

This efficiency is precisely why the column still is the undisputed champion of American whiskey production. For most bourbons and rye whiskies, the goal is a consistent product that can be produced at a scale that meets global demand. The column still is the perfect tool for that job.

It lets major producers create a clean, high-proof "new make" spirit that’s ready for the barrel. This process strips out many of the heavier, oilier congeners, which is a big reason why many American whiskeys have that characteristically smoother, and often sweeter, profile that many new drinkers find appealing.

Think about a powerhouse like MGP Ingredients in Indiana. They are one of the largest distillers in the country, churning out countless barrels of rye and bourbon for many of the most recognizable brands you see on the shelf. Their ability to maintain such a high level of quality and consistency across millions of gallons of whiskey is only possible because of their absolute mastery of the column still. This technology allows them to dial in the final spirit with precision, ensuring that the bottle of bourbon you buy today tastes exactly like the one you'll buy next year. The column still isn't just a piece of equipment; it's the very foundation upon which the modern whiskey industry was built.

How Each Still Creates a Unique Flavor Profile

Alright, let's get to the good stuff. We're moving past the mechanics and into what really matters: how the still shapes the whiskey in your glass. This isn't just an engineering choice for the distiller; it’s a fundamental artistic decision that defines the taste, aroma, and even the feeling of the spirit on your tongue.

Think of it this way. A pot still is like a seasoned cast-iron skillet. It’s a bit rustic, a little inefficient, but it locks in deep, complex flavors and lets the raw character of the ingredients shine. A column still, on the other hand, is more like a modern convection oven—it’s built for precision, purity, and a perfectly consistent result every single time. Both can make something incredible, but the final product is worlds apart.

The Pot Still Flavor Blueprint: Congeners and Complexity

The soul of a pot-still whiskey is its texture and depth. Because the batch process is less about purification, it allows a higher concentration of congeners—a cocktail of oils, esters, and other organic compounds—to make it into the final spirit. These aren’t flaws; they are the literal building blocks of flavor.

This heavy congener load translates directly to what you experience:

- Aroma: Pot still whiskies often have a big, booming nose. You’ll find earthy, nutty, and malty notes from the grain itself, mingling with fruity esters that can range from crisp apples and pears to rich, tropical notes.

- Taste: The flavor is almost always bold and full-bodied. The grain character—be it the spice of rye, the sweetness of corn, or the biscuity quality of barley—is front and center.

- Mouthfeel: This is the big tell. These whiskies are often described as oily, viscous, or chewy. They coat your palate with a weight and texture that spirits from a column still rarely achieve.

This isn't an accident. The slow, less "efficient" nature of the pot still is a feature, not a bug. It's designed to create a spirit that proudly wears its agricultural heart on its sleeve.

The Column Still Flavor Signature: Purity and Finesse

A column still is engineered to do the exact opposite. Its continuous operation is designed to methodically strip out many of those heavier congeners. As the vapor rises and condenses on each plate, it's essentially being re-distilled over and over, resulting in a spirit that’s significantly lighter and higher in proof.

Here’s how that efficiency shapes what's in the bottle:

- Aroma: The nose on a column-distilled whiskey is typically cleaner, more delicate. You're more likely to pick up light floral notes, vanilla, and caramel—aromas derived more from the barrel aging process than the raw grain.

- Taste: The palate is generally smoother and softer on the entry. The rough edges have been rounded off, creating a profile that many new drinkers find more approachable.

- Mouthfeel: The texture is noticeably lighter. Instead of that oily coating, the whiskey feels crisper and cleaner, often with a quicker finish.

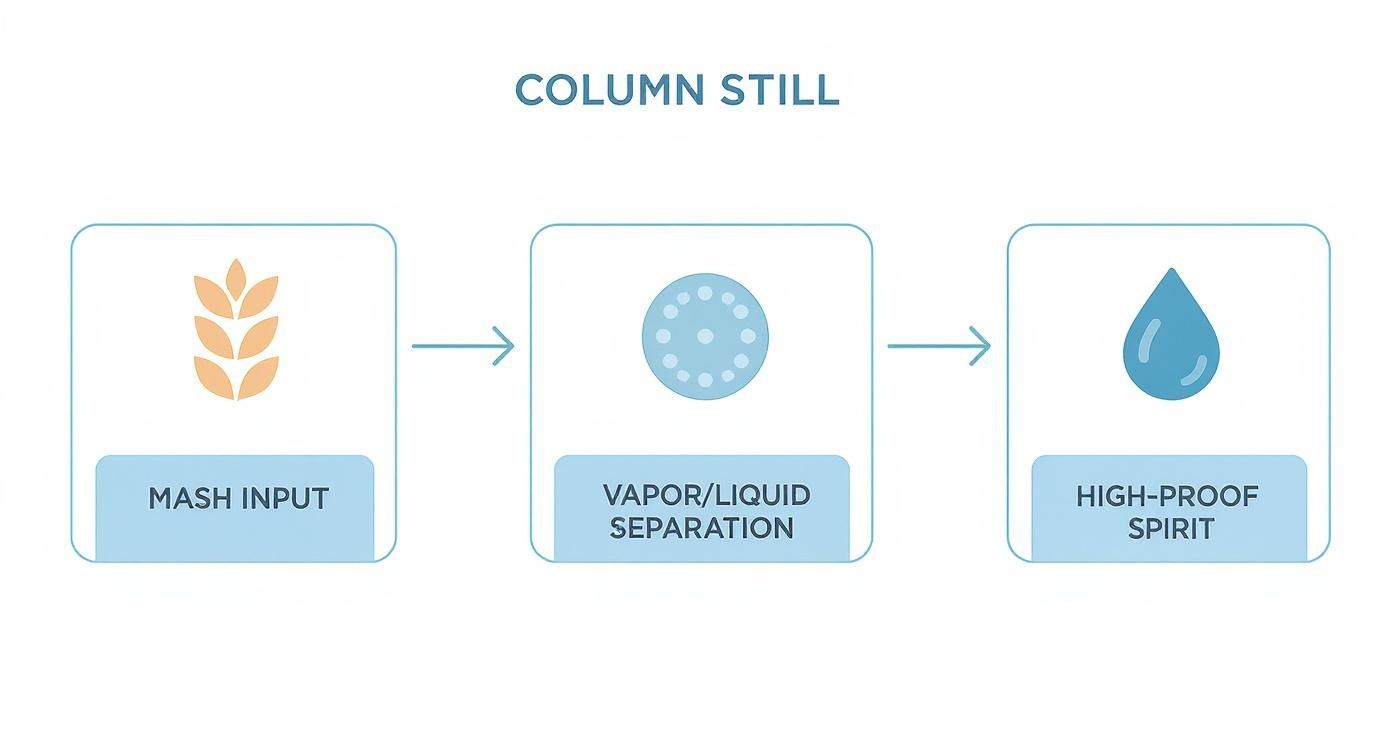

This infographic gives a simple look at the column still’s continuous journey, from mash input to the final, high-proof spirit.

That streamlined trip up through the perforated plates is precisely why the final spirit is so clean and consistent.

"A column still gives us precision and control, allowing us to create a consistent, clean canvas that lets the barrel do the talking. A pot still gives us a more expressive, grain-forward spirit right off the bat. It's about choosing the right tool for the story you want to tell."

This choice often comes down to tradition and market demand. Countries famous for traditional single malts, like Scotland and Ireland, lean heavily on pot stills for their iconic, complex profiles. Meanwhile, here in the U.S. and up in Canada, column stills are workhorses, efficiently and consistently producing the massive volumes of rye, bourbon, and grain whiskies that drinkers love.

The Best of Both Worlds: American Craft Hybrid Stills

In the freewheeling world of American craft whiskey, the pot-still-versus-column-still debate isn't always so clear-cut. Many smaller distillers are blurring the lines by using hybrid stills. These clever designs merge a pot still base with a rectifying column on top, giving them incredible versatility from a single piece of equipment.

A distiller can run it like a traditional pot still to get that rich, congener-heavy spirit. Or, they can engage the column's plates to produce a lighter, cleaner spirit. It’s a game-changer for craft producers who need to be nimble.

A great example is Colorado's Laws Whiskey House. They use a custom-made hybrid still to create their acclaimed four-grain bourbons and rye whiskies. It allows them to fine-tune the distillation, capturing the robust character you’d expect from a pot still while achieving a level of refinement that elevates their grain-forward style. It’s this kind of thoughtful approach that connects the raw ingredients, like the grain and yeast, directly to the final flavor. If you want to dive deeper into that connection, you can unlock the magic of yeast in our detailed guide.

By embracing this middle ground, distillers like Laws are crafting uniquely American whiskies that honor tradition while pushing the boundaries of what's possible.

A Distiller's Bottom Line: Artistry vs. Economics

Beyond the romance of flavor profiles and mash bills, the choice between a pot still and a column still is a cold, hard business decision. Distillers are constantly walking a tightrope, balancing the unique character they want in their spirit against the unforgiving realities of production economics. This single choice has a ripple effect, influencing everything from the initial startup cost and daily labor to whether the brand can ever scale up.

A small craft distiller launching their passion project might lean into the pot still because of its inefficiencies. The hands-on, batch-by-batch process gives them an almost obsessive level of control over every single drop. This allows them to create a truly expressive, singular whiskey that can carve out a niche in a very crowded market. It's a clear bet on character over sheer capacity.

On the flip side, a massive global brand needs ironclad consistency. For them, a column still isn't just an option—it's an absolute necessity. It’s the only way to churn out millions of liters of whiskey that taste exactly the same, whether you’re pouring a glass in Kentucky or Kyoto.

The Pot Still: A Calculation of Craft

Committing to a pot still means committing to a certain philosophy of production. The distiller gets ultimate control over the final spirit, but that control comes with a hefty price tag in operational terms.

- Pinpoint Control: The real magic of the pot still is the ability to make hyper-precise "cuts"—separating the heads, hearts, and tails of the run. This is how a distiller meticulously shapes the congener profile, essentially hand-crafting a spirit that is one-of-a-kind.

- Lower Efficiency: Pot stills are all about the batch process. Every single run has to be started, stopped, emptied, and cleaned. This means a much, much lower volume of spirit gets produced each day compared to a still that runs continuously.

- Higher Labor Costs: That constant cycle of starting and stopping requires a lot more hands-on attention from the distillery crew, which drives up the labor cost baked into every single bottle.

This trade-off makes perfect sense for a distillery like St. George Spirits in California, one of the original pioneers of the American craft movement. Their pot stills are the heart and soul of their operation, allowing them to create their iconic American single malt—a whiskey celebrated for a unique complexity that you simply couldn't replicate on a column still.

For a craft producer, the higher cost of pot distillation is a direct investment in the whiskey's personality. They are selling a unique story and flavor profile that commands a premium price, justifying the less efficient process.

The Column Still: The Engine of Scale

The column still is built around a completely different set of priorities: efficiency, consistency, and the ability to scale up—massively. The initial investment can be staggering, often far more than for a pot still, but the long-term operational savings are undeniable.

The numbers don't lie. Industry data shows that a 12-inch diameter column still can be nearly four times as efficient as a 500-gallon pot still, yet both require about the same number of people to run them. This means column stills pump out vastly more spirit per man-hour, crushing operational expenses and making large-scale production financially possible. But there's a trade-off in the barrel. A pot-distilled bourbon might hit its sweet spot in about two years, but the lighter spirit coming off a column still often needs an extra year or so to build comparable depth. You can dive deeper into the fascinating trade-offs in whiskey still operations.

This is exactly why the column still is the undisputed backbone of major distilleries. It allows a brand like Jack Daniel's to maintain its legendary flavor profile across tens of millions of cases every year. That consistency isn't just a production goal; it's a core brand promise. For new whiskey drinkers, this is a huge plus, ensuring the bottle they tried and loved will be the exact same every time they buy it again. Ultimately, the pot still vs column still debate often comes down to this: one is a tool for singular creation, the other is a machine for flawless replication.

A Tasting Guide for New Whiskey Drinkers

Alright, time to put all this knowledge into practice and train your palate. It’s one thing to understand the mechanics of a pot still versus a column still, but identifying their fingerprints in a glass is a skill that will seriously deepen your appreciation for the craft. For new whiskey drinkers, this is where the real fun begins.

The secret is to focus on texture and weight first, then hunt for flavors. These sensory cues are your roadmap back to the still. When you take a sip, just pay close attention to how the whiskey feels as it moves across your tongue.

Spotting the Still in Your Glass

Learning to pick out distillation style is really just an exercise in paying attention. Start by looking for these general characteristics, which almost always point to one method or the other.

- Pot Still Cues: A heavier, oilier, or more viscous mouthfeel is the biggest giveaway. These whiskies feel like they coat your palate. They often have robust, earthy, and grain-forward flavors with a complex finish that seems to hang around for a while.

- Column Still Cues: Look for a lighter body and a cleaner, crisper texture. The flavors are often more delicate and refined, letting barrel notes like vanilla and caramel take center stage over the raw character of the grain. The finish is typically smooth and quick.

Tip for New Drinkers: The most reliable tell is the texture. If it feels weighty and oily, think pot still. If it feels light and clean, think column still.

Your First Side-by-Side Tasting

The absolute best way to lock this in is with a direct comparison. This simple tasting exercise will make the differences between a pot still and a column still immediately obvious.

- Pot Still Pour: Grab a bottle of Irish Single Pot Still whiskey, like Redbreast 12. This style is famously made using pot stills and is celebrated for that creamy, full-bodied texture we've been talking about.

- Column Still Pour: Pour a classic American bourbon known for its column distillation, such as Buffalo Trace or Evan Williams. These are perfect examples of smooth, approachable, and barrel-forward whiskies.

Taste them one after the other, focusing on the differences in weight, mouthfeel, and how long the finish lasts. This little experiment is one of the fastest ways to build your palate. If you want to get the most out of it, check out our full guide on how to properly taste whiskey, which covers everything from nosing to finishing.

American Craft Whiskies to Explore

Once you’re comfortable telling the difference, start seeking out American craft distilleries that proudly showcase their still type. A great place to start is with a pot-distilled bourbon from a producer like Kings County Distillery in Brooklyn. Tasting it next to a classic Kentucky bourbon reveals a richer, bolder expression of America’s native spirit. This kind of hands-on exploration is the most rewarding way to appreciate the art of distillation and, more importantly, figure out what you truly enjoy.

Common Questions & Quick Answers

Let's tackle some of the most common questions that pop up when whiskey fans start talking stills. These are the quick-and-dirty answers you need to clear things up and sound like you know your stuff.

Is One Still Type Better Than the Other?

Nope. Neither still is inherently “better”—they’re just different tools for different jobs.

Pot stills are all about creating complex, flavorful, character-rich spirits. Think of them as the go-to for most single malts and expressive craft whiskeys. Column stills, on the other hand, are the undisputed champions of efficiency and consistency, perfect for churning out the lighter, cleaner spirits needed for large-scale bourbons and blended whiskies. It all comes down to what style of whiskey the distiller is trying to make.

Can Bourbon Be Made with a Pot Still?

You bet it can. While the vast majority of bourbon is made with column stills for sheer efficiency, a growing wave of American craft distillers is embracing the pot still.

This older method creates bourbons that are often richer, oilier, and more full-bodied than their column-distilled cousins. If you see a bottle from a smaller producer labeled “pot-distilled,” grab it. You’re in for a treat.

Tip for New Drinkers: Trying a pot-distilled bourbon from a craft distillery is a fantastic way to taste the impact of distillation on a familiar spirit profile. It helps you understand how much the still itself shapes the flavor.

What Is a Hybrid Whiskey Still?

A hybrid still is exactly what it sounds like: a mashup of both designs. It typically starts with a pot still base but has a rectifying column bolted on top.

This setup gives distillers an incredible amount of flexibility. They can run it like a traditional pot still to capture tons of flavor, or they can engage the plates in the column to produce a lighter, higher-proof spirit. Many American craft distillers love hybrid stills because one piece of equipment can produce a whole portfolio of different spirits.

Ready to discover your next favorite American craft whiskey without the bias of a label? Blind Barrels sends you four unique, top-shelf samples every quarter so your taste buds can lead the way. Explore the fascinating world of small-batch distilling at https://www.blindbarrels.com.